Individual Poetry Project

Life is an inscrutable and unknowable thing, and yet humans have searched through the ages for the meaning to our existence. Sometimes, the best way to discover truths about life is through the lens of someone else’s life. In his last book before his death, New Addresses, Kenneth Koch explores his life in a semi-chronological order through the medium of poetry. The book captures a perspective on the essence of being human through both sardonic wit and mature analysis, along with skillful and beautiful language.

To begin, New Addresses speaks to its audience through a refreshing new style: the apostrophe. The apostrophe, or letter poem, is a poem written in the form of a letter to a person, place, thing, or idea. Most of Koch’s poems are written to an abstract concept, although some are written to an object which may be a symbol for a broader idea. For example, some of the 50 poems in the book are addressed to fame, to “my fifties,” to the Italian language, to life, and to stammering. The poems in the book loosely parallel the author’s life. The book begins with “To Yes,” a complex poem that digs into the meaning of human existence, and what happens at the end of life. The following poem, “To Life,” follows the same theme, speaking to and personifying the state of living. The book then switches from the abstract to the more personal, as Koch explores his childhood in the next few poems, “To the Ohio,” “To My Father’s Business,” “To Piano Lessons” and “To Stammering.” Both subtle and bold opinions about these topics appear in the poems. The speaker gently praises the Ohio, revealing that he once kept a scrapbook about the river, but the speaker strongly reacts to his father’s business, saying “I thought I might go crazy in the job.”

The tone of the book changes throughout, and the next few poems demonstrate this especially well. These poems deal with Koch’s young adult years, as in “To My Twenties” and “To World War II.” This set of poems combines lovely language, cultural references, and personal experiences to create a beautiful and distinctive mix of words. Koch comments on more general themes in his and others’ lives, including poems that deal with sexuality, like “To Testosterone,” as well as identity, like in “To Jewishness” and “To My Old Addresses.” The author’s life in poems progresses into middle age, as seen in “To My Fifties,” and his attention turns to more practical concerns. These letters are sent to the fallible body, such as “To My Heart as I Go Along” and “To Breath.” As the author delves into more spiritual territory once more, his poems showcase fears and wonderings about the end of life, seen in poems like “To the Unknown.” As Koch eloquently outlines his own feelings and doubts, he intuitively gives words to the whole human experience. He closes the volume with “To Old Age,” a poignant take on the nature of getting old.

In New Addresses, Koch’s style is markedly mature, yet playful, as he wrestles with multi-faceted themes. He works within a simple style, the letter poem, which provides stability and ties together the poems with a common theme. Starting with this common foundation, Koch has room to cover many topics and use unusual styles of address. The letter poems, written in first and second person, draw the reader into a more intimate embrace of language. Since they use the pronoun “you” to speak with the topic of the poem, the reader may feel like she is being addressed. Nearly all of these poems are a page long or less, so they are bite-sized for a reader. However, this does not mean that they are easy to understand. The poems about childhood present their language and content in a fairly straightforward manner, mirroring the simplicity of a child. The poems set in Koch’s young adult life use more angst and stream of consciousness, as he had to face problems that were more complicated, sometimes even life-threatening. Changes in tone such as these help ease the reader through Koch’s different stages of life. Koch distinguishes his poems from others by their organization as well. All of the poems in this collection are written in one long stanza, except for two poems, both of which have two stanzas. On the page, the poems look like a splat of a solid idea, and the short, dense poetry is a joy to read. The poems are written in free verse, but they hide rhythm and rhyme in their depths.

Under analysis, the poems in the book use language in surprising ways to address interesting topics, which appeals to a wide audience with their artistry and simple humanity. The book begins with “To Yes,” a poem about the nature of words and of the world beyond the physical world. The poem is one stanza and is written in free verse. It is far from prose, however. It begins directly addressing the concept of “yes” in the second person, but digresses from this. What follows is a long middle section that explores the many uses of the word yes, and comes full circle in the end by addressing the concept “yes” personally once again. The central theme of the poem appears through questions, emerging eventually as a celebration of the affirmation and mystery of “yes.” Linguistic devices help energize the poem. Though it is written in free verse, the poem still has rhythm incorporated. In the lines “Pamela bending before the grate/…I will meet you in Boston/At five after nine,” a distinct hint of anapest rhythm comes through. The repetition of “yes” throughout the poem, besides contributing to rhythm, adds a sense of expectation, of waiting for the positive response to the multiple questions posed. The personification of the word “yes” seems at once to bring the poem within reach, and yet take some things out of the realm of comprehension.

A poem that is set in the middle of Koch’s life is the poem “To the Roman Forum.” The speaker of the poem invites the reader into his moment of intense joy, as his wife has just given birth to a baby, Katherine. Feeling spellbound and a bit disoriented, the speaker in this poem speaks in short, confused bursts, such as “Oh my, My God, my goodness, a child, a wife.” The sheer joy of the moment comes through in the unrefined words that abandon convention. While this poem is not heavy with figurative language, as befits the moment, the speaker does make an effective implied simile, comparing his excitement level to drinking 25 espressos. The poem ends with a comment on the timelessness of moments of wonder and great joy, saying “I am here, they are here, this has happened./ It is happening now, it happened then.” In a poem toward the end of the collection titled “To Scrimping,” Koch uses line lengths and enjambment to communicate his experiences with scrimping. The shorter line lengths communicate strong emotion, as the reader’s eyes jump to the next line quickly. For example, the lines “I need to have engraved in my cerebrum/as in a library wall” communicate frustration. Sentences take up between two and four lines, as Koch expertly varies the pace and the mood of the poem. The enjambed line “I am a tire with my wheel dependent on you, Scrimping,/Then.” highlights the time qualifier “then” to show that the speaker intends to resort to Scrimping only in his most desperate times.

A poem that is set in the middle of Koch’s life is the poem “To the Roman Forum.” The speaker of the poem invites the reader into his moment of intense joy, as his wife has just given birth to a baby, Katherine. Feeling spellbound and a bit disoriented, the speaker in this poem speaks in short, confused bursts, such as “Oh my, My God, my goodness, a child, a wife.” The sheer joy of the moment comes through in the unrefined words that abandon convention. While this poem is not heavy with figurative language, as befits the moment, the speaker does make an effective implied simile, comparing his excitement level to drinking 25 espressos. The poem ends with a comment on the timelessness of moments of wonder and great joy, saying “I am here, they are here, this has happened./ It is happening now, it happened then.” In a poem toward the end of the collection titled “To Scrimping,” Koch uses line lengths and enjambment to communicate his experiences with scrimping. The shorter line lengths communicate strong emotion, as the reader’s eyes jump to the next line quickly. For example, the lines “I need to have engraved in my cerebrum/as in a library wall” communicate frustration. Sentences take up between two and four lines, as Koch expertly varies the pace and the mood of the poem. The enjambed line “I am a tire with my wheel dependent on you, Scrimping,/Then.” highlights the time qualifier “then” to show that the speaker intends to resort to Scrimping only in his most desperate times.

The formal elements of this poem were fairly subtle but contributed much to the overall effect of the poem. While this poem was written without a regular meter, rhyme weasels its way into the poem. The last four lines, wrapping up the poem, have an aabb rhyme scheme, with “all,” “wall,” “way,” and “away.” As the poem transitions into a more solid rhyme scheme, it reaches for resolution.

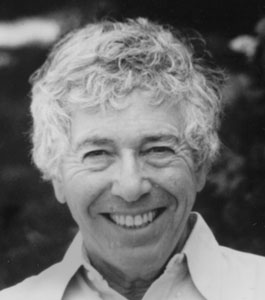

New Addresses is important in the poet’s works and life because it is his last work, and in many ways, it is the pinnacle of his poetry career. Kenneth Koch was born on February 27, 1925 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ohio and Koch’s childhood there make an appearance in this book, along with his military service, which he served from 1943 to 1945 in the Philippines. Koch lived in New York City for a time, where he became friends with John Ashberry, another famous poet. Together, they and other poets made up what came to be known as the New York School of Poets. Koch’s first book, Poems, was published in 1953. Many of Koch’s early works were humorous, a theme that continued throughout his career. He relished farce and satire, as his mock epic, Ko; or A Season on Earth, demonstrates. No classic was too good to be touched by Koch, as he also imitated “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Willams. In New Addresses, Koch covers new ground in his own life, such as his childhood and his military service. As Koch stated in an interview, “I was very surprised to find myself writing about these subjects. I was happy to find a way to write them.” (“New Addresses”).

In conclusion, New Addresses is a pinnacle in Kenneth Koch’s career, incorporating good-natured humor with astute observation about life, wrapped in beautiful language to create art. Through poem analysis and biographical information, a reader can better delve into the glittering sea of words. In some way, this book has improved the human condition, by touching the reader or by simply bringing more beauty into the world.